Engulfment and euphoria: The notebooks of Ellen Rogers

Cross posted from here

Like most writers, I have dozens of notebooks. But mine, unlike Ellen Rogers’, are not works of beauty. Most that survive are half-digested boluses of stickily crammed writing. Several are scantily inked, abandoned because of a rigid scheme I couldn’t maintain. I have notes on plays, novels and political party minutes, my son’s health needs. Notes for interviews, for which I religiously over-prepare. Critical studies on books and albums and films, often transcribed by the minute.

I prefer a plain paper. Best of all, give me an old-school, Silverline exercise book. 80 A4 white cheap pages, ideal for doodling, sticking visual prompts, writing in huge font and chucking remorselessly in the recycling.

My most personal are the worst-kept – if they escape the bin – in diaries from the Victoria and Albert or another museum of art, fashion or photography. Flicking through them, whatever the year, I see my big existential questions that never change; and travelling thoughts about travelling relationships that have long since left those pages.

Ellen Rogers is a photographer, artist, writer and academic, whom we’ve previously featured in The Demented Goddess. Her process feels worth recording in itself. Her visual field and practice marry analogue photography, painting, philosophy and politics.

Middle - a drawing by G. Franz, Pink image is by Laura Makabresku

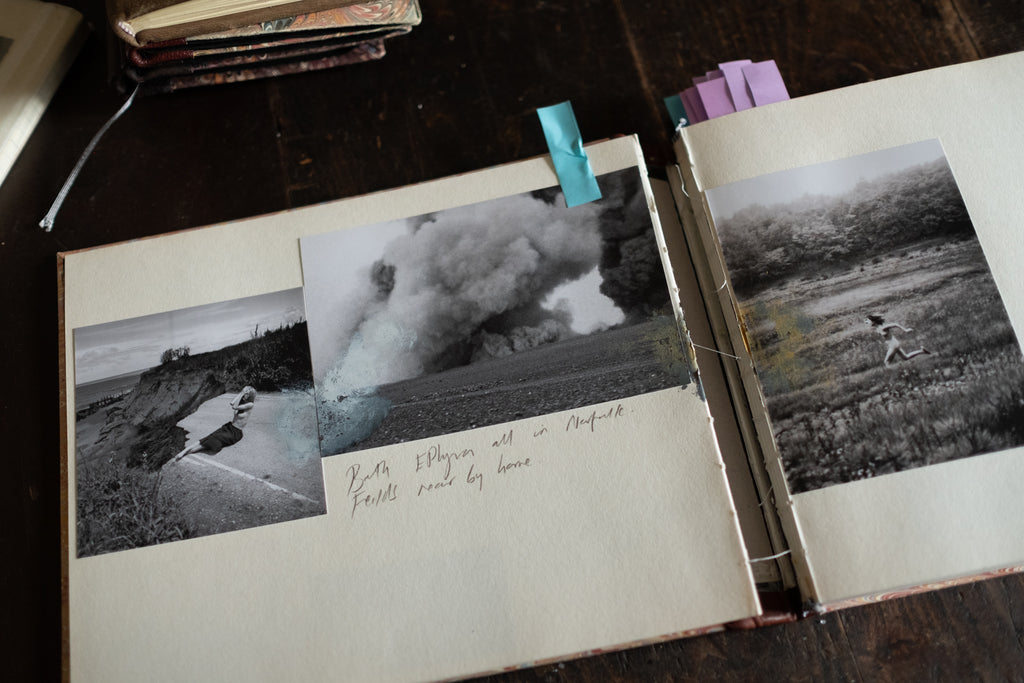

Here in these notebooks, we see Ellen’s ideas coming into being, taking flesh from the images and thoughts of others, or from an apparently superficial fashion shoot in which a nub of pain reveals itself. Here in this selection from her notebooks, we share a conversation while gawping at her pages. There is space here to drown. For, although inspiration is frequently mythologised as fleeting, wouldn’t we prefer to dwell in its catalytic spark forever?

DG: I often think about Sarah Bernhardt (below, centre). Sarah lying in her coffin bed to learn her lines; Sarah playing Hamlet; applying lipstick form her “stylo d’amour”; her friendship with the great Vedantic monk Vivekananda. Her interpretative skill as a sculptor is often forgotten beside the myth of Bernhardt the celebrated actor. Tell us about the flame-like pigment you’ve daubed over this central picture of her sculpture, ‘Ophelia’ – what were you thinking?

My relationship with Vivekananda is via another woman, Anne Beasant, a figure close to my heart. For her strange fluidity of radical leftist politics and unusual mystic tendencies, a Benjaminian character. I had no idea they both knew him. I’m wondering if he kept the company of a certain subset of fabulous women. The flames were literal, the drowning literal too. I was considering the engulfment of persecution. Not in a ‘cancel’ way, but in that condemned trend of womanhood. The constant vigilance of what it means to be a woman, how some people gate-keep that and how enfolding the experience is.

DG: What attracted you to these images of metamorphosis?

I like depictions of transformation, it’s liberating, no? To see something change. I often think of depression as stasis, a type of holding of the breath. The inability to breathe. In moments of its change or in moments when you see behind its curtain, you feel euphoria. I think a lot of my work is in conversation with that mode of change. Women running from that pain, women changing from one mode to another, women leaving a certain state or waking up to it or out of it.

Left – by Albert Watson for Prada 1989, Middle – Still from Penda’s Fen by Alan Clarke, right – by Odd Nerdrum

Left, Zoltan Toth

DG: “So, you have this island, you know? So what will you do about it?” (Derek Jarman) – what WILL you do about it, Ellen?

Quite!! What will I? I was processing these images because of topics like Brexit, the overt rainy miserabilism of England and the racism it was unearthing. With the unsettled earth of the UK now unturned, we are left with the foulness of the stench of stagnant conservatism that laid often just out of sight.

I think conversations and work on the topic is vital, we must confront it, keep unearthing it to confront it. I don’t always feel I’m the person best equipped to articulate this. But I do try.

DG: These images make me think how disaster can be a kind of release. How about you?

Well, that’s exactly it. When you are dealing in trauma or disaster, you are really asking how best do we deal with these topics and how can we better understand them. I’m not endorsing anxiety as a method. I’m not saying we need to eventuate everything terrible in order to cope. It’s more the case that understanding pain helps you relate to others. It helps you move on.

Left, by Anne Brigman, Middle, Alamy stock image, Right, by Dan Bumbas

DG: What draws you to palor and sepia and drapery?

I study fashion really, I think I’ve always been studying fashion, in photography, in images I collect, even as an academic, I study fashion.

I think about the textures of drapery, about Ebenezer Scrooge tugging at his bed curtains in horror at the atrocities he’s inflicted. In the folds of Edward Weston’s photograph of a Cabbage Leaf that looks like a veil or a dress. In Oscar Gustave Rejlander’s Two Ways of Life, I think of the drapes on the central figure and how they are incorrectly in focus when they should be just hazy enough to fit the correct depth of field. I fall in love with the dangerous folds of fabric in the erratic and erotic masterpiece ‘Flaming creatures’ by Jack Smith. I think of the history of window displays and the gendered ambiguity of the bohemian or flaneur, the master of the city and drapery. I love that actually.

Left, unidentified, Middle, Stalker by Andrei Tarkovsky, Right, Still from L’Albero degli zoccoli by Ermanno Olmi.

All photos by Paolo Roversi bar bottom left, by Steven Meisel.

Ellen Rogers was in conversation with Soma Ghosh

Follow Ellen @EllenJRogers and Soma @calcourtesan on Twitter

Leave a comment: